Estimated reading time: 4 min

Exploring Vernacular Architecture

Vernacular architecture refers to the local architectural styles using traditional construction techniques and materials of a region. This sort of architecture is often striking among the more homogenised modern styles and reveals a lot to its observers about the culture and character of the communities that developed it. It is important for modern architects to consider the materials and techniques of vernacular architecture, as it is often linked to environmental sustainability for its intuitive use of local materials, and social sustainability, as you will see from the breakdowns below that many examples of vernacular architecture are found in community buildings that bring together generations after generations of people. In this article, we will look at some of our favourite examples of these traditional, regional styles.

Minangkabau Architecture | Western Sumatra Indonesia

The traditional houses of the Minangkabau group of Sumatra have finials formed at the peaks of their huge concave roofs. Formed from thatch, bound by decorative metal bindings and drawn into points said to resemble buffalo horns as an allusion to a legend concerning a battle between two water buffaloes from which the “Minangkabau” name is thought to have been derived. The roof peaks themselves are built up out of many small battens and rafters. The houses, called Rumah Gadang, are constructed from renewable and farmable building materials, such as bamboo, palm fibre and wood.

Shinto Architecture | Japan

Shinto shrines are permanent Buddhist shrines of Japan built completely with Hinoki Cypress timber and bamboo frameworks without any nail or glue. The most easily identifiable feature of a Shinto shrine is the gabled roof, but other common features include elaborate gates, a fountain, decorative stone lanterns and guardian lion-dogs known as Komainu. Prior to the Buddhist construction of permanent shrines, Japanese shrines were temporary structures built for a particular purpose. Much of the vocabulary for Shinto architecture is therefore Buddhist in origin.

Sudano-Sahelian Architecture | West Africa

Perhaps best exemplified by the Great Mosque of Djenné, the indigenous architecture embraces sand and earth-based mortar to create sun-baked bricks, which are then coated in mud to give a smooth, sculpted aesthetic. The smooth mud-plastered surfaces are pierced with wooden support beams. These beams act as a scaffold for the necessary reworking of the buildings, which is done at regular intervals and involves the local community. There are four recognised substyles of Sudano-Sahelian architecture, which are Malian, Fortress, Tubali and Volta Basin.

Stave Churches | Norway

Stave churches are medieval wooden Christian religious buildings that are most commonly found in North-western Europe. All but two surviving stave churches now reside in Norway.

Stave churches of Norway combine Christianity, Nordic designs and Viking motifs in their architecture, and got their name from the post and lintel construction using load-bearing ore-pine posts called stafr in Old Norse, which adapted to Stav in modern Norwegian.

Maori Architecture | New Zealand

The Maori are indigenous Polynesian people who settled in New Zealand in the 1300s. One of their most recognisable architectural contributions is the Wharenui or “Big House” which is the communal house or meeting house of a community. The structure of a wharenui often symbolises an ancestor from the community. The koruru at the point of the gable on the front of the wharenui represents the ancestor’s head, the maihi (diagonal bargeboards) signify arms, the tāhuhu (ridge beam) represents the backbone, the heke (rafters) are the ribs and within the structure, the central column, the poutokomanawa can be interpreted as the heart.

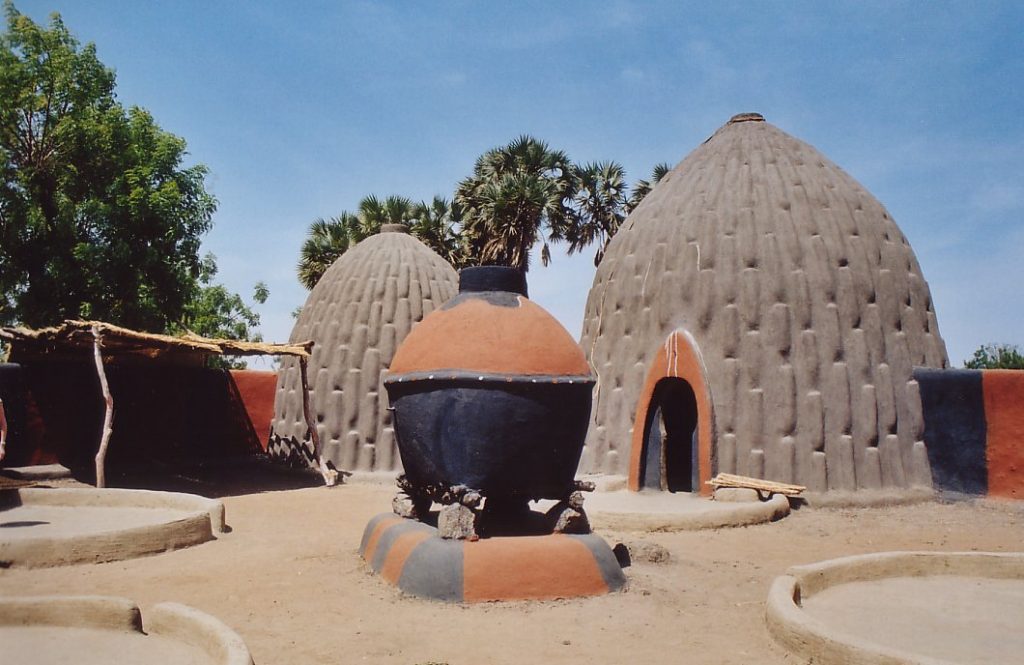

Musgum Mud Huts | Cameroon

Geometrically arranged reeds are covered in mud to produce the domestic mud huts of the Musgum people. The huts are built in the form of a catenary arch and in order to construct the complete 9-meter-tall arch, as well as to maintain it, the geometry of the facade creates practical footholds. Though now out of fashion, Musgum mud huts were once the most popular buildings in Cameroon due to their low cost and high efficiency. A small circular opening at the top of the huts also helps with air circulation and is used as an escape hatch if subjected to flooding. This circular opening, a few inches in diameter, also known as a smoke hole, is closed with a slab or a pot during the rains to prevent water from entering the house. Entrance is provided by a single door, which is narrow up to knee level, but widens at shoulder level, and is said to resemble a keyhole.